In today’s world, where trends come and go with lightning speed, fast fashion has become the go-to industry for affordable, trendy clothing. Major retailers release new collections multiple times a season, encouraging consumers to purchase more than ever before. The accessibility and low prices of these garments have made fashion more democratic, but beneath this glossy exterior lies a growing crisis with severe environmental and social consequences. This blog dives deep into the fast fashion phenomenon, exposing the hidden costs of this industry—from resource depletion and pollution to labor exploitation—and explores emerging solutions that aim to transform a business model built on disposability into one aligned with sustainability and ethics.

Fast fashion thrives on rapid production cycles and low manufacturing costs, relying heavily on synthetic fibers like polyester derived from fossil fuels, along with vast quantities of water, energy, and chemicals. The environmental footprint of producing just one kilogram of textile is staggering: it can require thousands of liters of water and release significant greenhouse gas emissions. For example, cotton cultivation alone uses about 20,000 liters of water per kilogram, often in regions already facing water scarcity. Moreover, dyeing and finishing processes involve hazardous chemicals that pollute waterways in manufacturing hubs across Asia, affecting both ecosystems and communities. When garments are discarded, they contribute to mounting textile waste, with millions of tons ending up in landfills or incinerators annually, where synthetic fabrics can take centuries to decompose, releasing microplastics and toxins.

Environmental damage, however, is only one facet of the fast fashion crisis. The industry’s reliance on cheap labor in developing countries has resulted in widespread human rights abuses. Garment workers—predominantly women—often face unsafe working conditions, long hours, and wages far below living standards. High-profile disasters, such as the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh, which killed over 1,100 workers, spotlighted the brutal realities behind clothing labels. Despite some progress through international accords and corporate pledges, enforcement remains inconsistent, and many workers still lack adequate protections and bargaining power. The pressure to produce massive quantities quickly and cheaply drives suppliers to cut corners, exacerbating labor exploitation and health risks.

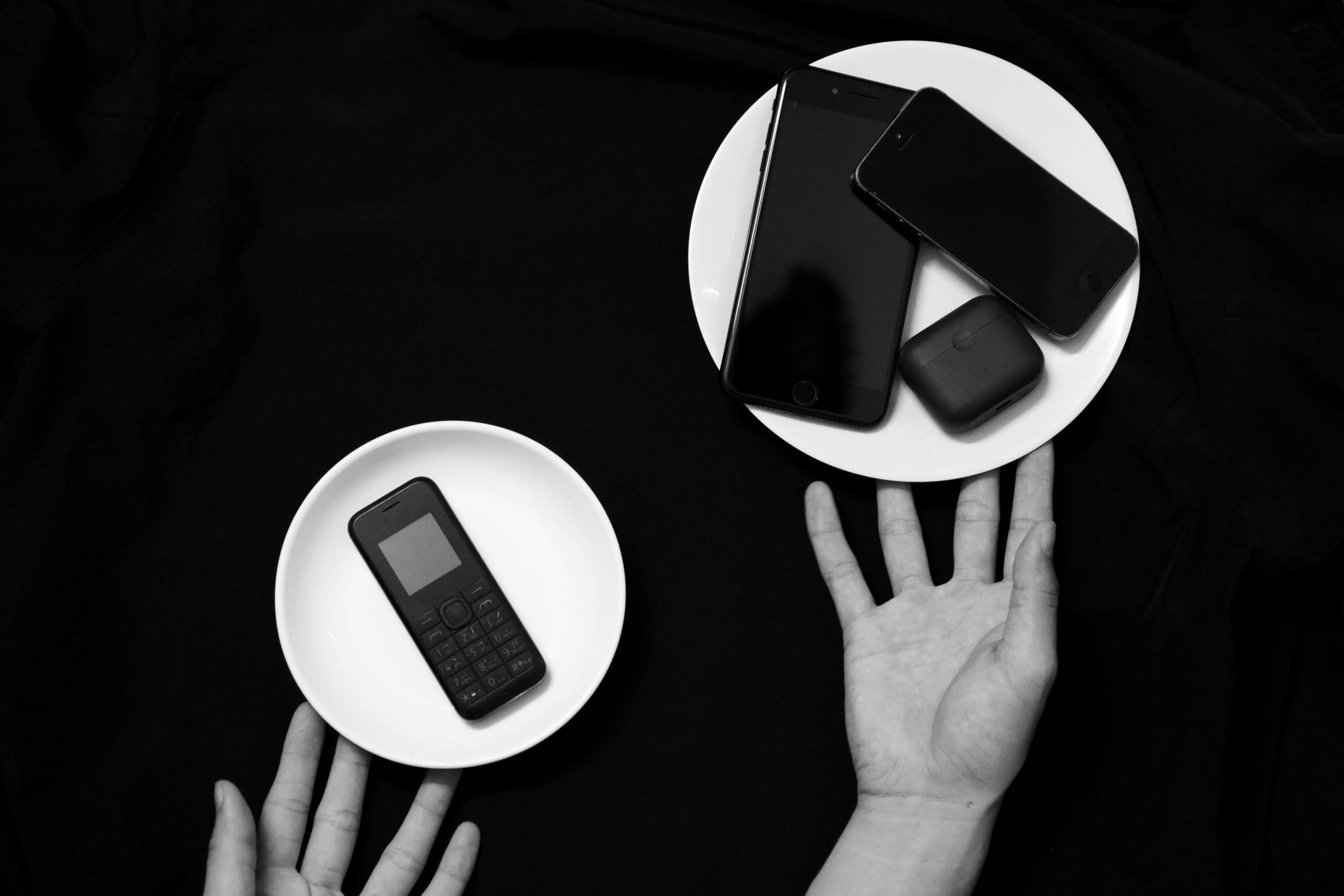

Fast fashion also fuels a culture of disposability and overconsumption. Marketing strategies encourage consumers to buy frequently and discard garments after only a few wears. Globally, clothing consumption has doubled in the last 15 years, but the average number of times an item is worn before being thrown away has dropped significantly. This trend intensifies environmental impacts and creates social pressures, as individuals feel compelled to constantly refresh their wardrobes to keep up with trends. The pandemic initially disrupted this cycle, leading some to embrace minimalism and secondhand shopping, but overall consumption remains high, driven by aggressive advertising and the allure of low prices.

Efforts to address the fast fashion crisis have taken many forms. Some brands are experimenting with sustainable materials, such as organic cotton, recycled polyester, and innovative textiles made from waste products like food scraps or algae. These materials reduce resource use and environmental harm but often come with higher costs and scalability challenges. Transparency initiatives, such as supply chain audits and sustainability reporting, aim to hold companies accountable, though critics argue that many fall short of meaningful change. Circular economy models, promoting garment repair, resale, and recycling, offer pathways to extend product life cycles and reduce waste, but require shifts in consumer behavior and infrastructure investments.

Consumer activism is playing an increasingly important role. Movements advocating for ethical fashion, slow fashion, and “buy less, choose well” philosophies are gaining traction. Social media campaigns expose irresponsible practices and elevate alternative brands committed to sustainability. Additionally, secondhand markets and clothing rental services are expanding, providing more sustainable options and challenging the dominance of fast fashion. However, the transition toward more sustainable consumption faces barriers, including affordability, convenience, and awareness gaps.

Government policies and international frameworks can accelerate change by setting minimum labor standards, environmental regulations, and incentives for sustainable practices. Some countries have introduced laws to combat textile waste, such as France’s ban on destroying unsold clothing. Trade policies and international cooperation are also critical given the globalized nature of fashion supply chains. Public procurement policies favoring sustainable textiles and corporate due diligence laws could further shift industry incentives.

Innovation in technology is beginning to transform fashion production and consumption. Digital design and 3D printing enable more efficient, customized manufacturing with less waste. Artificial intelligence supports demand forecasting and inventory management, reducing overproduction. Blockchain offers tools for supply chain transparency, helping consumers verify sustainability claims. Yet technology alone cannot solve systemic issues; it must be embedded within a broader commitment to ethical values and systemic reform.

In conclusion, fast fashion’s allure comes at a steep environmental and social cost. The industry’s model of rapid production and consumption strains natural resources, pollutes ecosystems, and exploits vulnerable workers. Addressing these challenges requires a multi-dimensional approach involving brands, consumers, governments, and innovators working collaboratively. By embracing sustainability, transparency, and ethical labor practices, the fashion industry can evolve from a driver of crisis into a force for positive change. The choices we make as consumers, policymakers, and businesses today will determine whether fashion’s future is one of disposability or durability, exploitation or equity, harm or healing.

Leave a Reply